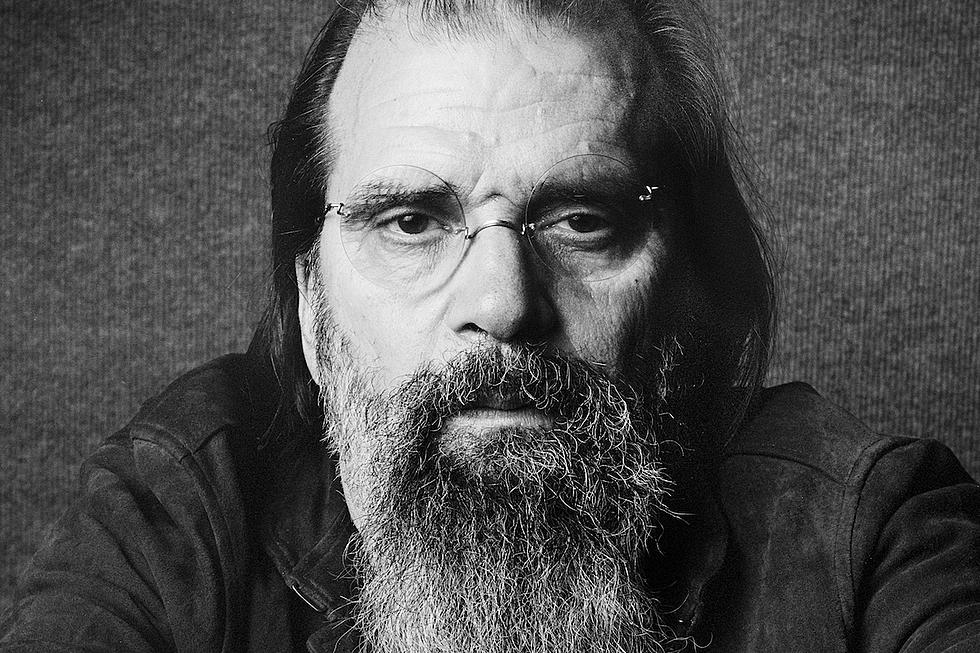

Interview: With ‘Ghosts of West Virginia’, Steve Earle Wants His Subjects to Feel Heard

"I wish I was at Caffe Reggio."

Steve Earle is in Tennessee, about 800 miles away from the historic Greenwich Village coffee shop. Though he is a New Yorker through and through — he's lived in the city for 15 years — in mid-March, Earle found himself packing up and heading to his home in Tennessee as the city quickly became the American epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

"Hopefully I'll have a reconnaissance mission soon," he says. "I miss New York a lot. But once the play closed and my son's school closed, the best thing was to come to Tennessee."

The play that Earle mentions is Coal Country, which made its debut on March 3 at the Public Theater, two weeks before New York City shut down. Written by documentary playwrights Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen, Coal Country tells the story of the Upper Big Branch coal mine explosion that shattered the small, unincorporated community of Montcoal, W. Va., on April 5, 2010; 29 of the 31 miners present died.

Blank and Jensen approached Earle, a Virginia native, and asked if he'd lend a hand in the narrative. "I've made the 'preaching to the choir' record several times," Earle says of his oft-political voice finding its way into his music. "But I was actually looking for a way to make a record that spoke to and, maybe if I did it right, for some people who didn't vote the way that I did.

"I think that's what is killing us: Everyone is concentrating on how we're different rather than how we're the same," Earle continues. "Most people have more in common with everybody else than you'd think, and so, I was looking for how to go about making that kind of record, and then Jessica and Erik called and this fell into my lap."

The three of them traveled to West Virginia to interview the two miners who survived the explosion as well as the families of those who died. Blank and Jensen turned those interviews into the monologues that make up Coal Country, and Earle used them to craft 10 new original songs, seven of which serve as the guiding soundtrack for the musical (the other three tell broader stories of West Virginia not specifically connected to the explosion).

With the help of his band the Dukes — comprised of Chris Masterson on guitar, Eleanor Whitmore on fiddle, Ricky Ray Jackson on pedal steel, Jeff Hill on bass and Brad Pemberton on drums — these stories are brought to life and captured forever on Earle's new record, Ghosts of West Virginia, out Friday (May 22) via New West Records. The 29 men who died on April 5, 2010, are honored throughout the LP, but most powerfully and unforgettably in the astounding track "It's About Blood," in which Earle lifts his voice and names every single one of those miners.

"This is the beginning of a conversation that I think we need to have or we're f--ked," Earle says matter-of-factly. "As long as people like me keep believing everyone who voted for Donald Trump is a racist or is stupid, we're f--ked, because it's simply not true.

"People in West Virginia voted for Donald Trump because Hillary Clinton went to West Virginia and said she was going to close the coal mines. Trump heard that and he went there and said he wasn't going to," he adds. "The truth is, they were both lying; neither of them has the power to close the coal mines. You know who has the power to close coal mines? It takes all of us to decide we're going to do something else about energy."

As Earle makes that point, he realizes it still raises the question: What happens to the workers in West Virginia in the areas where the only people who have anything are working in coal mines?

"If you can't answer that question, nobody's going to f--king vote for you," he says. "People say that people vote their pocketbooks, but it's not even that. They're voting their livelihood; they're voting for taking care of their families."

Though his own personal politics may not line up with those of everyone in West Virginia, it didn't cause any issues during the interviews or the making of the album and musical. "My politics were no different when I made Copperhead Road," Earle says, "but the only difference back then was I had that weird, schizophrenic Texas thing where I was a gun owner, too."

He pauses and laughs at that statement, then adds, "I'm not a gun owner anymore."

For Earle, making big, bold statements about politics has never been something he's shied away from. In 2002, he released the profound Jerusalem, a record that became most well-known for its nod to John Walker Lindh — an American who aided the Taliban and was eventually captured as an enemy combatant — in the haunting "John Walker's Blues." Two years later, he dropped the in-your-face The Revolution Starts Now, which earned him a Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Folk Album.

Today, though, Earle realizes that type of record is not what's needed.

"This is chess, it's not checkers," he explains about Ghosts of West Virginia. "It's the beginning of the conversation I think we need to have about how we're the same rather than how we're different.

"Saying Trump is bad or an asshole, that's not going to solve anything. This record is a chance to talk about it, to have a conversation about this," Earle continues, "because right here in these songs, we're talking about the union, and that's a common ground between people in West Virginia and people in New York — a belief that trade unions have a place in and are a fundamental part of our democracy."

"I believe capitalism is fundamentally oppressive because it depends on the circles of labor to thrive," he adds, discussing his own socialist beliefs. "That's straight out of f--king Das Kapital; that's what those two big books say when you get right down to it. But say that in West Virginia? It doesn't mean s--t. All they know is that they had a union, and the people who had the coal jobs were protected and things were the safest they could be. And the union went away, and the jobs got dangerous. The money was still good, but they were working 12 hours a day, they had no healthcare, there were no safety inspections. And then people will sit around in an intellectual setting and say, 'Well, why are they voting against their own self interest?'"

Earle takes a breath to drive the answer to that question home: "Because Hillary Clinton said she was going to close the coal mines. That's it."

Earle understands that some people will look at him and not want to listen because he's a successful musician who lives in New York City, but that doesn't distract him.

"Yeah, I'm a privileged person. Not everyone has the chance to sit around Caffe Reggio and talk about politics, but I also understand why people are scared of all of this stuff that I believe," he says as he considers his own childhood of being taught to be terrified of Communists and the like. "I was raised to be anti-socialist; I believed with all my heart when I was 10 years old that if I encountered Nikita Khrushchev on the street that he would eat me. So I understand why people are scared of what I believe, but I also believe this presidency has done serious damage to the quality of our democracy, and we have to do something different. Something's not working."

Ghosts of West Virginia, Earle believes, is a step in the right direction to begin mending the disunity that has been so strongly cultivated over the last few years. From the opening words of "Heaven Ain't Goin' Nowhere" to the closing strum of "The Mine," Earle succeeds in not just starting this conversation, but crafting one of the most prophetic and powerful albums he's ever released.

"You know what I want to come out of this record? I just want people in West Virginia to know I hear them, to know that I give a f--k, that somebody who lives in New York City gives a f--k," he explains. "It's a baby step, but I think it's where you have to start."

More From 102.3 The Bull

![Nitty Gritty Dirt Band Enlist Jason Isbell, Rosanne Case + More for ‘The Times They Are a-Changin” [LISTEN]](http://townsquare.media/site/623/files/2021/02/nitty-gritty-dirt-band.jpg?w=980&q=75)